Inland Dry Port Financial Model

20-year Financial Model for an Inland Dry Port

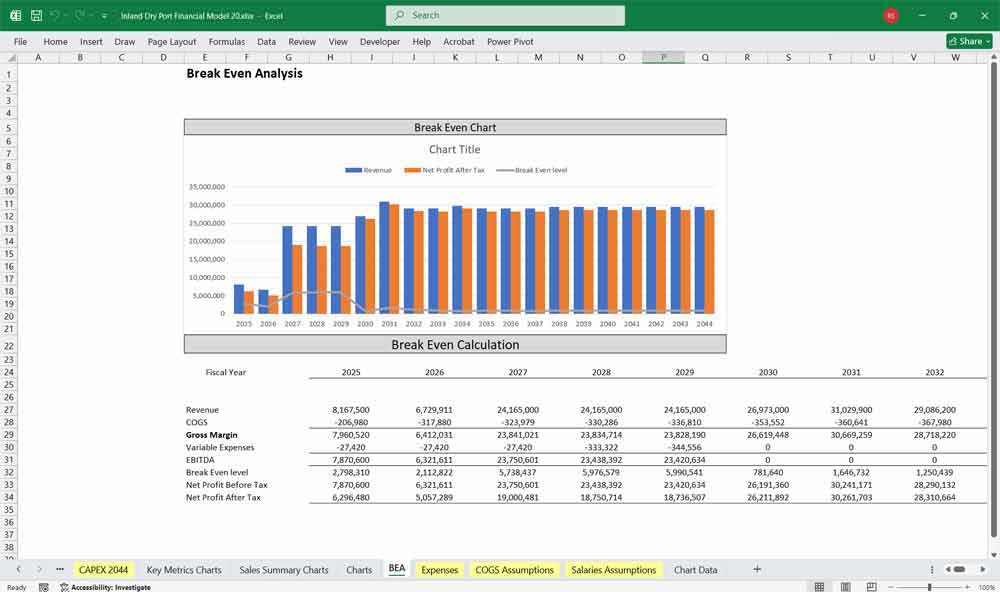

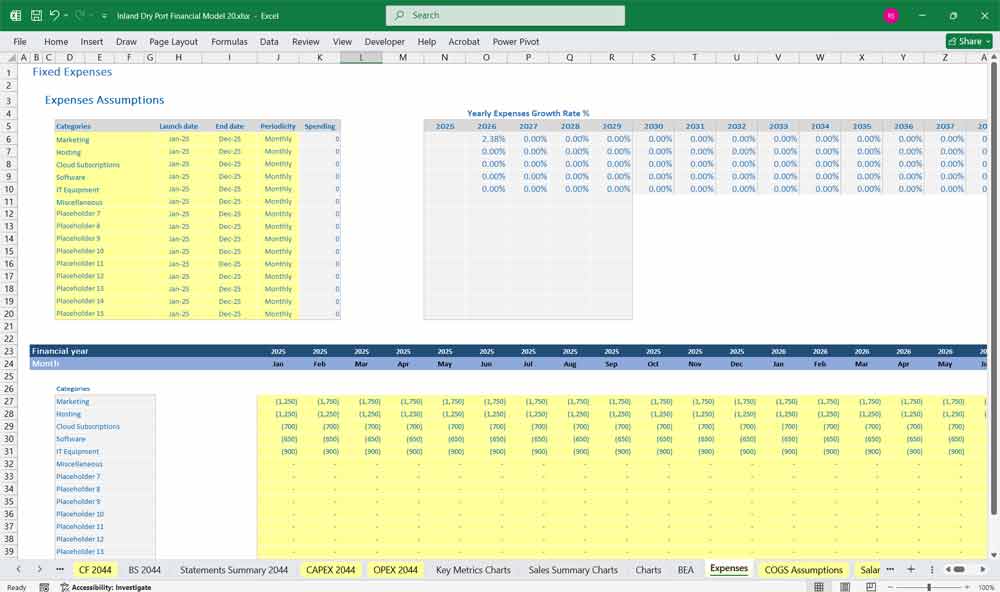

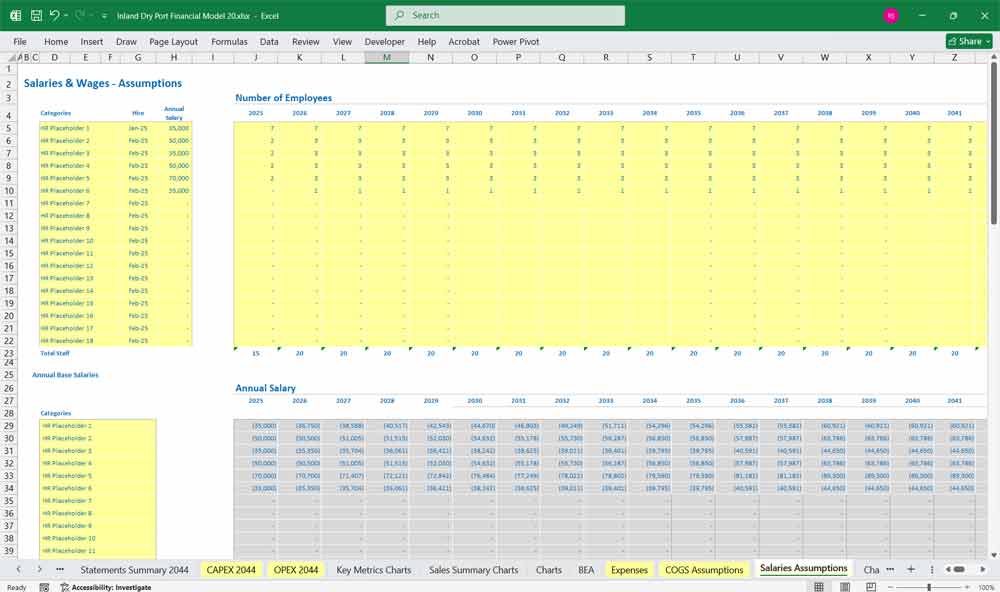

This very extensive 20 Year Inland Dry Port Model involves detailed revenue projections, cost structures, capital expenditures, and financing needs. This model provides a thorough understanding of the financial viability, profitability, and cash flow position of the Intermodal Freight Hub. Including: 20x Income and Cash Flow Statements, Balance Sheets, CAPEX and OPEX Spreadsheets, Excel Statement Summary Sheets, and Income Revenue Forecasting Charts with the specified revenue streams, BEA charts, sales summary charts, employee salary tabs and expenses sheets. Over 140 Tabs of financial data.

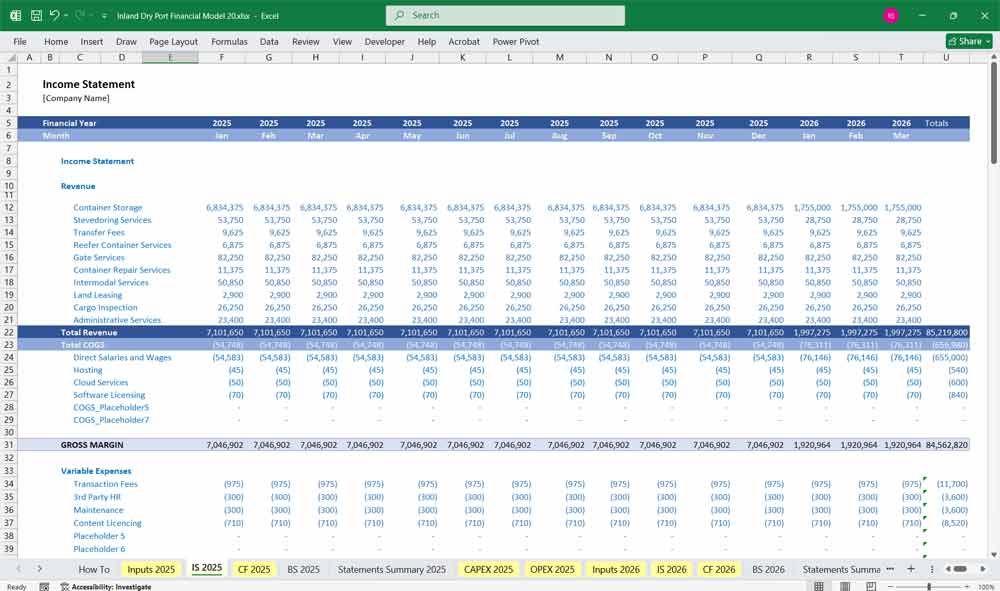

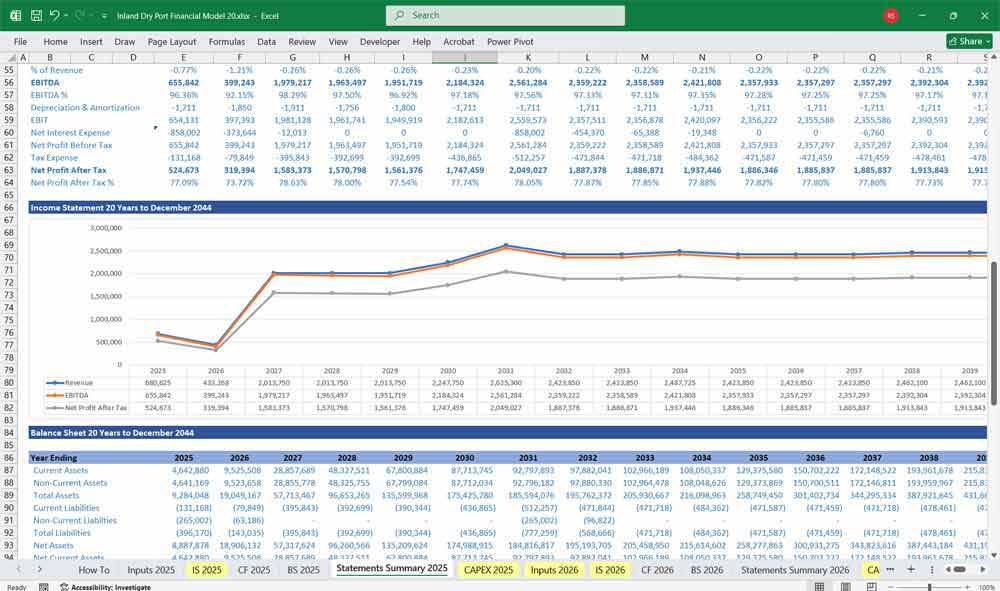

Income Statement

The Income Statement (or Profit and Loss Statement) projects the dry port’s revenues and expenses to calculate its net profit or loss. It focuses on the operating performance of the facility.

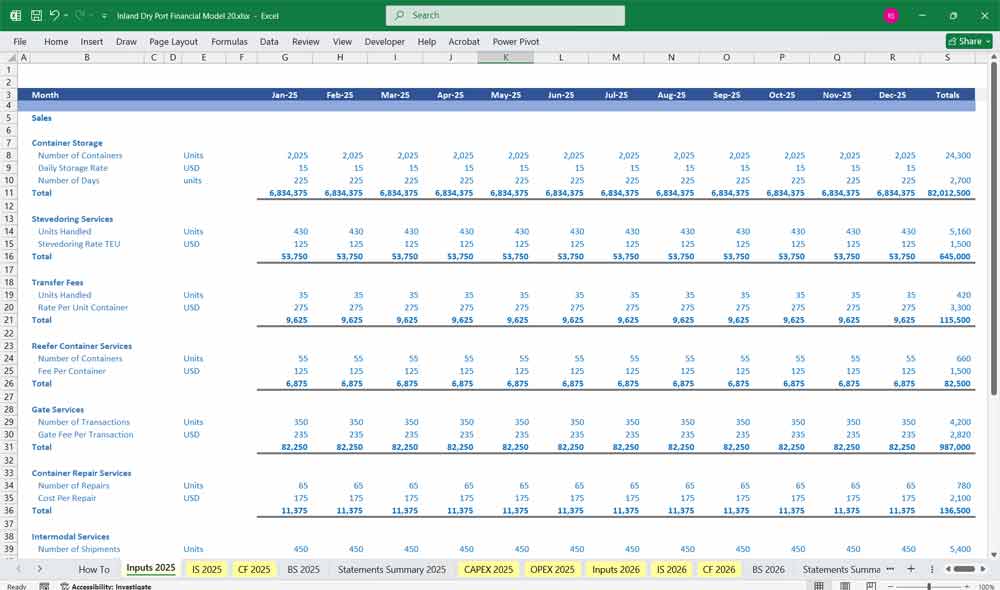

Revenues

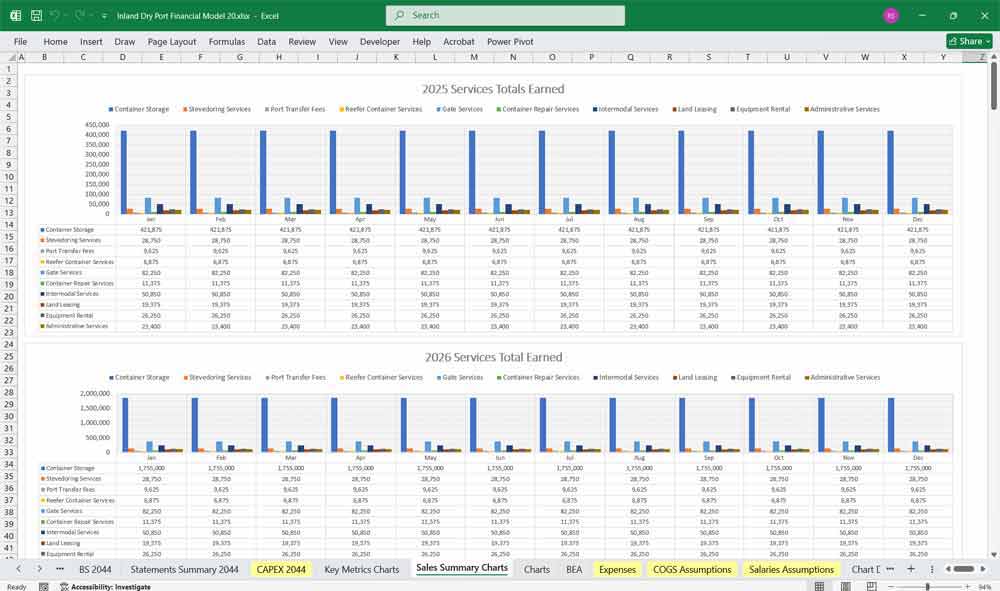

Revenues are the primary sources of income for the dry port. These can be broken down into various categories:

Container Handling Fees: This is the core revenue stream. It’s based on the number of containers handled, often categorized by type (20-foot, 40-foot, etc.) and the service provided (loading, unloading, stacking, etc.). The model needs to forecast container volumes, which are often tied to global trade forecasts and the port’s specific business plan.

Storage and Demurrage Fees: Fees for storing containers beyond a free grace period. This is a critical revenue source and depends on the dry port’s operational efficiency and customer behavior.

Customs and Inspection Fees: Revenue generated from providing customs clearance and inspection services.

Ancillary Services: Income from other services like container repair, maintenance, and cleaning.

Value-Added Logistics: Revenue from services like consolidation, deconsolidation, and warehousing of cargo.

Rail and Truck Handling Fees: Fees for transferring containers between different modes of transport (e.g., rail to truck).

Operating Expenses (Opex)

These are the day-to-day costs of running the dry port:

Labor Costs: Salaries and benefits for staff, including crane operators, administrative personnel, and security.

Utilities: Costs for electricity, water, and other utilities, which can be significant due to the heavy machinery.

Maintenance and Repairs: Costs to keep equipment (cranes, reach stackers, etc.) and infrastructure (pavement, buildings) in good working order.

Fuel Costs: Expenses for fuel used by forklifts, trucks, and other on-site vehicles.

Administrative and General Expenses: Costs for insurance, office supplies, software, and other general overhead.

Depreciation and Amortization

This non-cash expense accounts for the decline in value of the dry port’s assets over time. Depreciation is applied to tangible assets like cranes and buildings, while amortization is for intangible assets like software licenses.

Interest Expense

This is the cost of borrowing money to finance the project. It’s calculated based on the project’s outstanding debt balance and the interest rate.

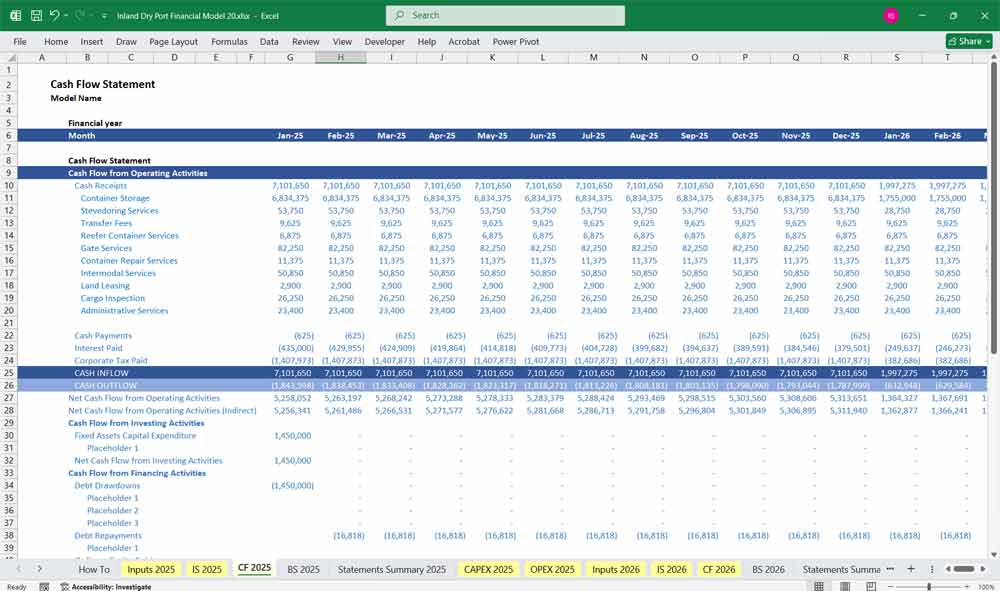

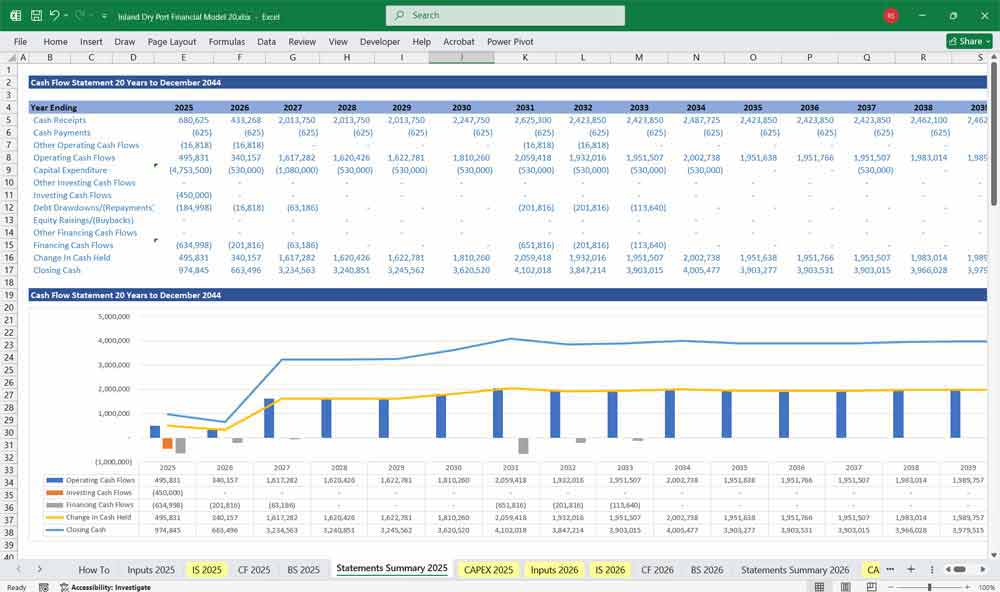

Inland Dry Port Cash Flow Statement

The Cash Flow Statement tracks the actual cash coming into and leaving the business. It’s arguably the most critical statement for a dry port project, as it reveals the facility’s ability to generate cash to pay back debt and fund operations. It’s broken down into three sections:

Cash Flow from Operations (CFO)

This section starts with the net income from the Income Statement and adjusts it for non-cash items (like depreciation) and changes in working capital (accounts receivable, accounts payable, inventory). It shows the cash generated from the core business activities.

Net Income: The starting point, taken from the Income Statement.

Depreciation and Amortization: Added back to net income because it’s a non-cash expense.

Changes in Working Capital: Adjustments for changes in operating assets and liabilities. For example, an increase in accounts receivable (money owed by customers) means cash was not collected, so it’s subtracted.

Cash Flow from Investing (CFI)

This section shows cash used for or generated from long-term investments.

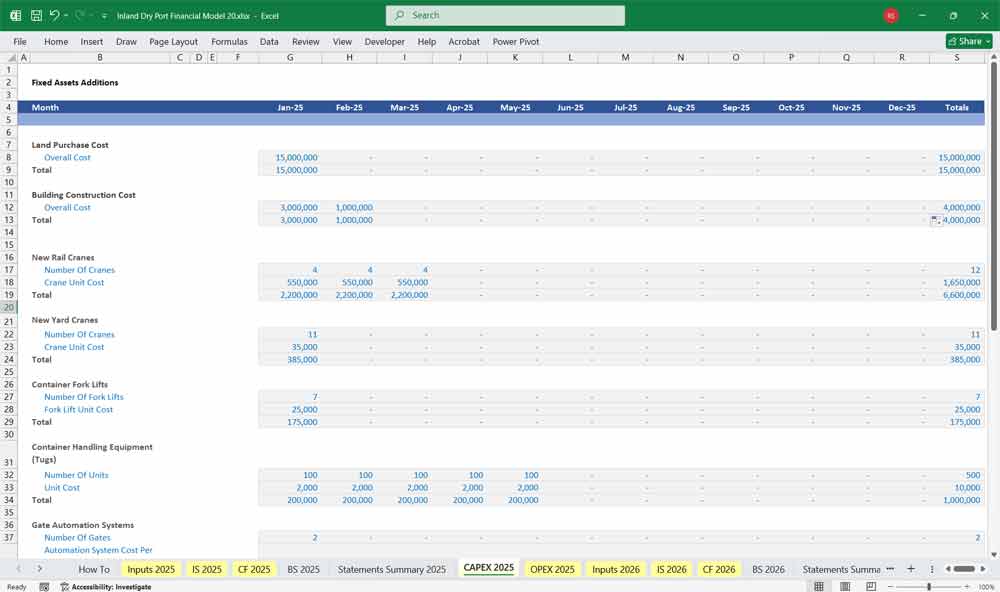

Capital Expenditures (CapEx): The cash spent on acquiring long-term assets. This is a major outflow in the early years of the project and includes the cost of land, cranes, office buildings, and IT infrastructure. The model must have a detailed CapEx schedule.

Sale of Assets: Cash received from selling any long-term assets.

Cash Flow from Financing (CFF)

This section details the cash flow related to financing the project.

Debt Issuance/Repayment: Cash received from new loans or cash paid to repay existing debt. This is crucial for calculating the debt service coverage ratio.

Equity Contributions: Cash injected into the project by investors.

Dividend Payments: Cash paid out to equity investors.

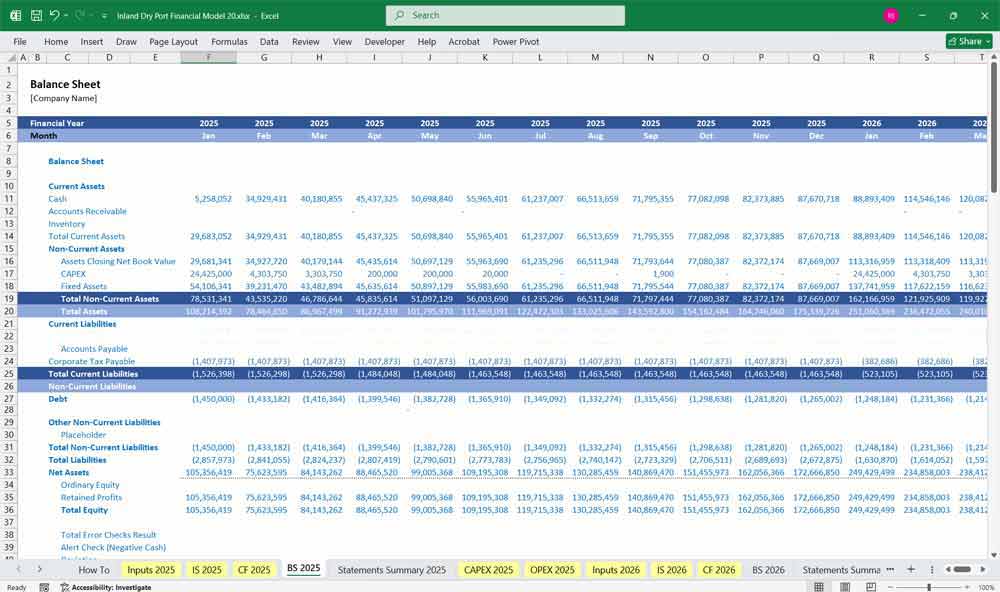

Inland Drop Port Balance Sheet

The Balance Sheet provides a snapshot of the dry port’s financial position at a specific point in time. It follows the fundamental accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity.

Assets

Assets are what the dry port owns. They are categorized as current and non-current.

Current Assets: Assets expected to be converted to cash within one year.

Cash and Cash Equivalents: The cash on hand. This is the ending cash balance from the Cash Flow Statement.

Accounts Receivable: Money owed to the dry port by its customers.

Inventory: Any spare parts or supplies on hand.

Non-Current Assets: Long-term assets used for more than one year.

Property, Plant, and Equipment (PP&E): This is the dry port’s main asset base, including land, buildings, cranes, and other machinery. This is a significant part of the model.

Liabilities

Liabilities are what the dry port owes to others.

Current Liabilities: Obligations due within one year.

Accounts Payable: Money the dry port owes to its suppliers.

Current Portion of Long-Term Debt: The portion of the long-term debt that is due within the next year.

Non-Current Liabilities: Long-term obligations.

Long-Term Debt: The principal balance of loans outstanding, net of the current portion.

Equity

Equity represents the owners’ stake in the dry port.

Paid-in Capital: The amount of money investors have put into the project.

Retained Earnings: The cumulative net income of the dry port, less any dividends paid out. This links the Income Statement to the Balance Sheet.

The model links these three statements. For example, the net income from the Income Statement flows into the retained earnings on the Balance Sheet and is the starting point for the Cash Flow from Operations. The CapEx from the Cash Flow Statement increases the PP&E on the Balance Sheet, and the ending cash balance from the Cash Flow Statement becomes the beginning cash balance for the next period and the cash balance on the Balance Sheet. This interconnectedness is what makes the financial model a powerful and dynamic tool.

20-year Inland Dry Port (Intermodal Freight Hub) Benefits

A 20-year financial model provides a long-term strategic outlook, which is crucial for an Inland Dry Port (Intermodal Freight Hub). The extensive time frame allows stakeholders to forecast the project’s entire lifecycle, from initial construction and ramp-up to mature operational years. This long-range perspective is essential for understanding the port’s sustained profitability, assessing the impact of long-term macroeconomic trends, and planning for future expansion or technological upgrades. It moves beyond short-term tactical decisions and focuses on the enduring value the facility will create.

CAPEX and Your Inland Dry Port

This 20-year model is essential for capital expenditure (CapEx) planning and financing. Dry ports require significant upfront investment in land, heavy machinery like cranes, rail infrastructure, and warehouse facilities. By projecting these costs over two decades, the model helps determine the optimal timing for capital injections, the scale of debt financing required, and the anticipated return on investment for equity partners. This detailed schedule of expenditures ensures that the project remains financially solvent and that funding is secured well in advance of key construction or upgrade phases.

Inland Dry Port 20-year Risk Assessment

A 20-year financial model is fundamental for risk assessment and stress testing. It allows developers and investors to simulate various scenarios, such as fluctuations in global trade, changes in logistics demand, or shifts in fuel prices. By running these stress tests, the model can identify potential vulnerabilities in the project’s financial structure and evaluate its resilience under adverse conditions. This proactive risk management approach helps in developing contingency plans and negotiating more favorable terms with lenders and insurers.

Inland Dry Port and Dept Repayment Structuring

The 20-year model is vital for debt repayment and investor return analysis. Lenders and equity investors need to be confident that the dry port can generate sufficient cash flow to service its debt obligations and provide attractive returns. A 20-year forecast provides a clear picture of the project’s Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR) and Internal Rate of Return (IRR) over its operational life. This detailed analysis is a cornerstone of the due diligence process and is often a prerequisite for securing project financing.

Inland Dry Port (Intermodal Freight Hub) Sale and Aquisition

Finally, a 20-year financial model aids in valuing the asset for potential sale or acquisition. As a dry port matures, its market value is heavily dependent on its projected future cash flows. The model provides a robust framework for discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis, which is the standard method for valuing such long-lived infrastructure assets. This makes the project more attractive to potential buyers and provides existing owners with a clear understanding of their asset’s value, facilitating smoother transitions of ownership.

Final Notes on the Financial Model

This 20 Year Inland Dry Port Financial Model helps focus on balancing capital expenditures with steady revenue growth from a vast range of Intermodal Freight Hub services. By optimizing operational costs, and efficiency, and maximizing high-margin services like container storage and gate fees, the model ensures sustainable profitability and cash flow stability.

Download Link On Next Page